Caregiver Support Services in US Healthcare: Gaps and Opportunities

Anyone caring for an older loved one with complex chronic conditions, disabilities, cognitive decline, or age-related frailties knows the practical, emotional, and financial challenges of being a family caregiver. From coordinating care with doctors and managing day-to-day challenges of helping with activities of daily living to keeping them socially active – this burden falls entirely on families. According to AARP, over 42M Americans currently serve as unpaid caregivers for older adults over the age of 50, and we estimate that 37M are caring for someone who is Medicare eligible.

Essentially, medical care is provided by the health system, but most social supports needed for these older adults fall to the families. This gap between medical care and social supports becomes more and more evident as the complexity of care increases. Let’s put this in healthcare terminology.

Long-term services and supports (LTSS) refers to a range of health-related services and supports needed by individuals who lack the capacity for self-care due to a physical, cognitive, or mental disability or chronic conditions. Specifically, within LTSS, home-and community-based services (HCBS) assist people with the activities of daily living (such as eating, bathing, and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (such as preparing meals, managing medications, and housekeeping). These services include personal care, adult day care, home health aide services, meals, transportation, home modification, assistive devices, or technology.

We have realities we should be aware of:

-

According to the HHS, 70% of people over 65 will require some type of LTSS – an expense not covered under Medicare or Medigap.

-

As health care and LTSS shift from institutional to home-based care, the burdens on family caregivers will likely increase without adequate support.

-

With rising home and institutional care costs and formal caregiver shortages, 66% of caregivers use their retirement and savings funds to pay for care (Genworth).

-

Greater reliance on fewer family caregivers also adds to costs borne by family members with increased emotional and physical strain, competing work demands, and financial hardships.

In this article, I detail the current state of caregiver support in Medicare Advantage, Traditional Medicare, and Medicaid, and highlight specific care models and areas of growth.

Rapid growth in Medicare Advantage enrollment but lags in LTSS support

Medicare Advantage is experiencing rapid enrollment growth.

Over the last decade, Medicare Advantage, the private plan alternative to traditional Medicare, has experienced rapid enrollment growth, reaching nearly 48% penetration in 2022 with roughly 28M enrolled members. 99.7% of Medicare beneficiaries have access to a Medicare Advantage plan as an alternative to traditional Medicare. The average Medicare beneficiary has a choice of 43 MA plans available for individual enrollment, offered by an average of 9 insurers. At the current growth rate, the share of all Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in MA is expected to reach 61% by 2032 (KFF).

Medicare Advantage plans compete for complex and lower income population.

Medicare-eligible enrollees fall into one of three broad plan types: Individual plan generally available to all (66% enrolled in 2022), Employer or Union sponsored group plan (18%), or Special Needs Plans (SNP) (16%) across Dual eligible D-SNP plan, Chronic C-SNP plan, or Institutional I-SNP plan.

In 2022, there was a 19% increase in SNP plans, indicating plans investment in managing high-risk, high-cost patients. There were 700 D-SNPs for people dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, indicating growth in high-need population, and 272 C-SNPs plans, most of which focus on people with complex chronic conditions. Medicare Advantage plans are banking that they can better manage this population by controlling for the two per-member revenue drivers: population risk and plan performance.

This growth in MA, especially in SNP, is relevant because Caregivers are 50% more likely to be caring for someone enrolled in a MA plan. Four in 10 caregivers are in high-intensity situations, providing care over 46 hours/week, assisting with 3+ ADLs and 5+ iADLs (AARP). – resembling a high risk, high-cost population.

Supplemental benefits not sufficiently funded to provide caregiver support.

MA plans offer supplemental benefits not covered by traditional fee-for-service Medicare. With the market nearing 50% penetration and increasing competition, once considered novel, these benefits have become table stakes as MA plans compete to attract new enrollees and retain existing ones. This is general exuberance from emerging companies with supplementary services as the go-to-market strategy – it is prudent to understand how these are designed at a higher level.

-

Most offered supplemental benefits include coverage for dental, vision, and hearing services, as well as wellness or fitness programs designed for healthy beneficiaries rather than populations with the most significant social or medical needs.

-

LTSS Supplemental Benefits are offered in two forms: (1) Primary health related that are offered uniformly to all enrollees and address services that address functional impairments (Adult Day Health Services, Home-based Palliative Care, Caregiver Supports, and In-Home Support Services) and (2) non-health special SSBCI (Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill) for the chronically ill that can be targeted benefits to enrollees based on disease state or socioeconomic status (Food and Produce, Pest Control, Transportation for non-medical needs, Social Needs Benefit and Home modifications). In 2023, only 1091 plans (~27%) offer In-home Support Services, and 293 plans (7%) offer support for Caregivers benefits, and while it varies from plan to plan, these benefits still need to be funded at sufficient levels.

-

Currently, CMS requires plans to report on enrollment but not utilization of benefits, so there isn’t good data available publicly. However, anecdotally, supplemental benefits experience low utilization primarily due to low member awareness and hurdles with member navigating their benefits.

-

Supplementals benefits are financed using rebate dollars. MA rebates are calculated as a portion of the difference between the FFS spending benchmark in each county and the plan bid in that county. Higher-quality plans receive a larger percentage of that difference. However, the rebate funding level limits the number and depth of funded benefits by a plan at any time. For 2023, rebates for MA plans (excluding employer plans and SNPs) average $196 per enrollee per month, which funds all benefits in a particular plan. Plans project that out of the $196 per enrollee per month, only $50 (26%) of rebates will be used for supplemental benefits, with the rest going to will go toward reductions in cost sharing for Medicare services like vision, dental, hearing, etc. (MedPac). As a result, LTSS benefits are unlikely to be funded at sufficient levels in individual MA plans.

SNPs plans are more likely to have more supplemental benefits.

This is because of risk adjustment dollars for managing high-cost, high-needs patients and other funding sources compared to individual MA plans. However, access to these benefits is required to demonstrate eligibility, which is often a navigational challenge for caregivers. This creates caregiver opportunities for care models to target D-SNP and C-SNP populations in supporting caregivers through care coordination/navigation, training, and support.

MA plans need to see evidence of impact on health outcomes.

Health plans recognize the need for caregiver engagement, and some plans are starting to put programs in place to have a Caregiver on File and are experimenting with programs to support caregivers. The STARS quality improvement and member experience and clinical/care management functions at a health plan need evidence of caregiver support models and their impact on healthcare utilization, outcomes, and member engagement. The lack of evidence data is holding back caregiver innovation programs in MA plans.

CARE MODEL #1 – Caregiver engagement in closing care caps

In this model, the Care Management at SNP plan engages family caregivers of high-cost, high-risk beneficiaries who need additional support at home. From getting them to annual wellness visits to remote data capture and medication compliance, family caregivers serve as an extension of the health plan’s care management, providing non-medical care in the home, assisting with closing care gaps, and driving improved compliance to care plans. The model could enhance member engagement and retain members in this increasingly competitive MA market while helping improve outcomes of these beneficiaries with complex needs.

Increasing popularity of value-based contracts.

The adoption of value-based care has accelerated in recent years, primarily driven in MA, and this trend could continue in the coming years as payers, employers, and the government embrace these models. Health plans increasingly seek to delegate/share risk to/with providers.

There are three categories of value-based care providers:

-

Risk-bearing primary care groups enter value-based care contracts with payers intending to take over the accountable care within capitated payments, either on professional and physician services or on a member’s entire cost of care. These providers often offer a higher-touch care model for a smaller patient panel than in fee-for-service primary care.

-

Value-based care MSOs have developed a compelling value proposition for independent primary- and specialty-care groups by facilitating the transition to risk through a combination of off-the-shelf tools and accompanying wraparound services, including payer contracting and practice transformation support.

-

Risk-bearing specialty groups, while currently less prevalent than their primary care counterparts, are increasingly carving out medical-cost risk in value-based models tied to their specific procedures and conditions.

Value-based care growth will continue to accelerate across all lines of business (MA, Original Medicare, Medicaid, Commercial, and ACA). The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) issued an ambitious goal to shift 100% of Medicare beneficiaries into an accountable care relationship by 2030.

CARE MODEL #2 – Wrap around Model

Populations generally delegated by health plans to providers in a value-based contract tend to have higher risk and high costs, with a higher reliance on paid home care and unpaid family caregivers. A caregiver support wrap-around model where the at-risk provider proactively engages family caregivers to support the member to reduce costly hospitalization and emergency visits improved engagement in care and closed gaps in care.

This model is an extension of model 1 above. It would involve some form of care planning, caregiver training & support, and incenting them to help close gaps in care ranging from getting them to annual wellness visits, health risk assessments, preventative vaccinations to medication compliance, and much more. This model of actively engaging family caregivers as an extension of the care delivery team has the potential to improve health outcomes of the patients while improving the financial performance of at-risk providers.

Traditional Medicare leans into Dementia Care Innovations with an Alternate Payment Model.

In a previous blog titled Moving the Needle on Dementia Care, I wrote about the high prevalence of caring for someone with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD), and the financial and emotional impact it has on family caregivers. Proper care for those diagnosed with dementia requires better coordination of care, seamless navigation across the multitude of providers, timely access to care and interventions, and supporting caregivers. Early CMS funded pilot projects of a comprehensive, coordinated care model demonstrated that managing the care of people with dementia can reduce hospitalizations and emergency department visits and delay nursing home placement, thus improving outcomes and reducing total costs.

CARE MODEL #3 – Guiding an Improved Dementia Experience (GUIDE) Model

On July 31, 2023, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced a new nationwide model – the Guiding an Improved Dementia Experience (GUIDE) Model – a model test that aims to support people living with dementia and their unpaid caregivers.

Through the GUIDE Model, CMS will test an alternative payment innovation model for participants (Part B provider in traditional FFS Medicare) that delivers key supportive services to people with dementia, including comprehensive, person-centered assessments and care plans, care coordination, and 24/7 access to a support line. Under the model, participants will assign people with dementia and their caregivers to a care navigator who will help them access services and supports including clinical services and non-clinical services such as meals and transportation through community-based organizations.

The GUIDE Model will also enhance access to the support and resources that caregivers need. Unpaid caregivers will be connected to evidence-based education and support, such as training programs on best practices for caring for a loved one with dementia. Model participants will also help caregivers access respite services, which enable them to take temporary breaks from their caregiving responsibilities.

The model will pay participants a per-beneficiary per month (PBPM) amount, also known as a dementia care management payment (DCMP), for providing care management and coordination and caregiver education and support services to beneficiaries and caregivers. DCMP rates will be adjusted by a Health Equity Adjustment (HEA) and a Performance Based Adjustment to incentivize high-quality care. GUIDE will also pay for a defined amount of respite services for a subset of model beneficiaries.

Kudos to CCMI efforts in supporting Caregivers and those living with ADRD with this comprehensive care model that bridges clinical care and social support. One can only expect to see this program being adopted by Medicare Advantage in the future and even applied to other complex chronic conditions with a disproportionally high impact and reliance on family caregivers for care.

Medicaid leads the way in HCBS.

As of July 1, 2021, the total Medicaid enrollment is over 90 million, and 72% of all Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in comprehensive managed care organizations (MCOs), making Medicaid managed care the dominant delivery system for Medicaid enrollees (KFF).

Medicaid managed care delivers Medicaid health benefits and additional services through contracted arrangements between state Medicaid agencies and MCOs that accept a set per member per month capitation payment for these services. This is an alternative to a fee-for-service model where the state pays providers directly for each covered service received by a Medicaid beneficiary.

As states expand Medicaid managed care to cover newly eligible beneficiaries and those with greater needs and higher costs, the share of Medicaid dollars going to MCOs could continue to increase.

Medicaid is the primary payer for LTSS, paying $216 billion or 54% of $400 billion+ spent in 2020 on LTSS in the U.S. With $245 billion in total HCBS spending in 2020, HCBS makes up more than half of all spending on LTSS, with Medicaid share of $162 billion spent on HCBS (KFF). It is estimated that 4 million people used LTSS delivered in home and community settings (KFF)

Nearly all states now provide support for family caregivers. Almost all (49) states offer at least one family caregiving support in their HCBS programs, and 39 states offer more than one family caregiving support. These supports frequently include respite care (49 states), caregiver training (33 states), and caregiver counseling/support groups (24 states), and 15 states offer other services that include assistive technologies, housing, and support services, safety & prevention services, etc. For all types of waivers, respite care was the most frequently reported support.

CARE MODEL #4 - Self-directed Care Programs with MCOs

Getting paid as a family caregiver is one of the most frequent questions in online and offline forums by financially strapped caregivers. As part of LTSS, states support enrollees with long-term care needs through waiver programs to self-directed Medicaid programs (also known as consumer-directed care programs or participant direction programs), allowing family members to get paid for providing care. It’s the ability and right for a person with a disability to actively make choices in assessing their needs, determining the caregiver to meet those needs, and evaluating the quality of services provided.

States have developed and expanded consumer direction programs over the past decades. Given increasing interest in home and community-based care over institutional care, consumer direction programs are a growing option to offer older adults and people with disabilities an alternative to institutionalization. In the self-directed model, the beneficiary chooses their caregiver and manages all day-to-day tasks. Self-Direction is an alternative method of care delivery that ensures that patients receive the care they’re entitled to while maintaining control and jurisdiction of their care plan.

How does it work – MCOs may appoint a Financial Management Services (FMS) provider company to assist individuals and their families. FMS providers can help with payroll and employer-related duties, such as withholding and filing taxes, purchasing insurance, and issuing payroll checks. If a family caregiver selected by the member is providing self-directed care, they are responsible for providing care as the member directs and according to the schedule the member established and gets the training they need based on program requirements.

We see the promise of a tech-enabled platform to help MCOs drive utilization in self-direction to:

-

drive awareness and educate members and families.

-

enroll qualifying members in self-directed programs.

-

assist member and caregiver with payroll, withholding and filing taxes, budgeting, and payroll.

-

assess care needs of member and developing a care plan for caregiver to follow.

-

train caregiver based on program needs.

-

reporting on program compliance performance (e.g., electronic visit verification)

The number of individuals enrolled in self-directed programs has grown in the last few years. The 2019 inventory found 1.2M individuals enrolled in self-directed programs nationally, with California enrollments accounting for nearly half (49%) of the national total (AARP). We are seeing tech-enabled platforms that streamline and scale the awareness and utilization of such self-directed care models especially in MCO managed populations.

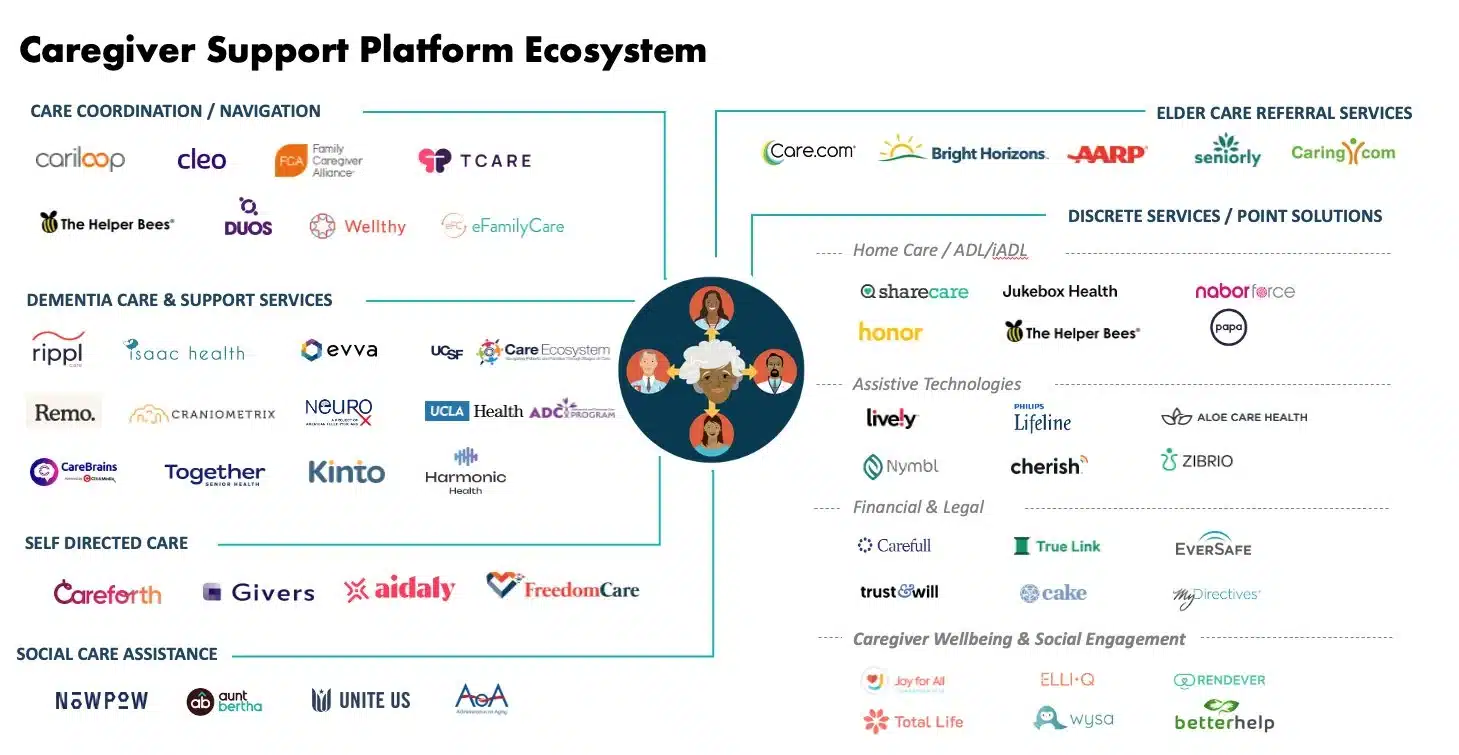

In the last few years, the Caregiving and AgeTech ecosystem has been quite vibrant with D2C services that address specific challenges of older adults and B2B2C care models that help health plans, employers, and providers support its members/employees/patients and their caregivers.

While discrete point solutions address specific needs, companies looking to scale programs in healthcare should be mindful of emerging care models that are financially well-aligned with health plans, improve outcomes, and enhance member engagement to support caregivers.

Explore our healthcare solutions.